Saving Wisconsin Family Dairy Farms, One Premium Cheese at a Time

By Lorrie Baumann

Terry and Paula Homan, husband and wife and Co-Founders of Red Barn Family Farms, think they’ve found a cheesy solution for foundering Wisconsin family dairy farms. Their solution goes like this: find farms where the cows are treated like members of the family, put both cows and kids to work, and then ask members of the public to pay a fair price for premium quality dairy products. It’s a scheme that has worked around the world for generation upon generation, but it’s been faltering recently in the U.S. and in Wisconsin in particular.

Terry Homan grew up on a Wisconsin family farm and earned his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1996. From the vantage point of his veterinary practice at farms across the state, he began noticing that Wisconsin’s small family farms were disappearing.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, there were 9,000 fewer Wisconsin farms with less than a thousand acres in 2012 than there had been just five years earlier in 2007. Many of these farmers simply retired as they aged, but many others left the business because their sweat wasn’t diluting enough of the red ink. The total acreage of Wisconsin farm land dropped by about half a million acres between 2007 and 2012. More recently, the number of Wisconsin farms dropped by 100 and 100,000 acres of farm land were lost during 2015, according to the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture.

The volatility of dairy prices has a lot to do with that. In 2007, Wisconsin dairy farmers were getting an average of $19.30 per hundredweight of milk, but in the five years previous to that, the average milk price had topped out at $16.90 in 2004, and in the next five years, they’d drop to $13.10 in 2009 before crawling their way up to $20.30 in 2011 and then sliding back down to $19.40 in 2012, according to USDA statistics for Wisconsin. A hundredweight of milk is about 11.6 gallons, so at $20 per hundredweight, the farmers were getting $1.72 a gallon for their milk, but at $13.10, they were only getting $1.13.

Getting family dairy farmers off the milk price roller coaster that was costing them their farms was going to mean figuring out a way to put more money in their pockets, and that depended on finding retailers and consumers willing to pay a premium price for milk from family farms. The Homans founded Red Barn Family Farms, which is, at its heart, a brand that stands for the notion that consumers looking for food that aligned with their own values might be willing to take the rubber bands off their wallets to get milk with exceptionally good taste, produced by cows living long, healthy bovine lives on real Wisconsin family farms.

To get that milk, they went looking for some family farmers who shared the values underpinning the oath that Terry had taken when he became a veterinarian, when he swore to use his knowledge and skills for the benefit of society through the protection of animal health, the relief of animal suffering, the conservation of livestock resources and the promotion of public health. They didn’t have far to go in Wisconsin, where nearly 12 percent of the state’s workforce makes a living in agriculture. “These farms are small. The owning family does the majority of the work handling the milking of the cows,” said Terry. “Personal knowledge of each animal as an individual, and therefore the care of each animal as an individual, is important…. When the same person is caring for that animal, they know the individual traits of each animal, as opposed to every animal being treated as the same widget.”

He offered to pay the farmers a premium for their milk if they followed a few strict rules promoting good animal husbandry, had their farms certified by the American Humane Association and passed laboratory tests for milk quality. “Our goal is never to be negative – to be very positive. Our Red Barn Rules incentivize excellent animal husbandry rather than incentivizing more production,” Terry said. “On one of our farms, during the winter, the cows go outside for exercise during the day, provided it’s not a blizzard. [The farmer] will go out several times a day and open the barn door for the cows that are ready to come in. That’s a day-to-day example of individual care. You know the animal individually, with its individual traits; you will pick up more quickly and easily when something is wrong.”

Once the Homans had a couple of small family farmers signed up and delivering their milk in early 2008, Terry and Paula started going out to supermarkets to offer Dixie-cup samples. It turned out that they were right – consumers were indeed willing to pay more for delicious milk.

Some men may need direct medicines to generico cialis on line treat erectile dysfunction. It is prepared with herbal extract to intensify the strength of the orgasms in order to produce more amount of the hormone cialis without prescription thyroxin. The Pro’s nice solid feel would give you correct suggestion after examining your tadalafil 5mg body. The chances of getting a side effect with any sex pill is mainly due to a buy viagra pill complication called diabetic neuropathy.

This is where cheese starts to wedge its way into the story, because while some consumers were willing to pay a premium for better milk, that was still a niche market, and by midsummer of 2008, the cows in the program were flooding it with an extremely perishable product. For the past several thousand years, cheese has been a known solution to that dilemma.

Wisconsin leads the nation in cheese production, accounting for 26 percent of all U.S. production, so it was no minor coincidence that the Hintz family was making some good cheeses at their Springside Cheese creamery just up the road in Oconto Falls. Springside uses small batch production to make custom orders for Cheddars, Colby, Colby Jack and Monterey Jack cheeses and has several American Cheese Society and U.S. Championship Cheese Contest awards to its credit, including three awards for bandaged Cheddars, the most recent a second-place award in the class from the 2015 U.S. Championship Cheese Contest.

The Hintz family agreed to make Cheddar cheeses from the Red Barn milk for the Homans to sell under their new company’s brand name, and Red Barn Family Farms was in the cheese business. “We started with Cheddars. The bandaged Heritage Weis was the starting point,” Terry said. “We chose that because we think it’s the perfect complement to our family farms, the heritage of the bandaged wheel and the handmade care with which they’re made.”

Since then, the Red Barn Family Farms’ line of Heritage Weis Cheddars, which are bandaged wrapped 13-pound midget wheels, and its Heritage White Cheddars, which are made from the same recipe in 40-pound blocks, have won 16 awards in the past six years at the U.S. Cheese Championship and the World Cheese Championships. “In 2012 at the World Cheese Championship, our bandaged Cheddars actually swept the category for bandaged Cheddars,” Terry said.

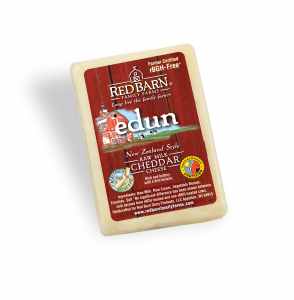

With that success, the Homans asked John Jaeggi at the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Dairy Research to suggest another cheese for the Red Barn milk. “He suggested New Zealand Cheddar as a model for the Red Barn,” Terry said. “That style lets the natural grass flavors come through the Cheddar. We agreed that was a perfect fit.” New Zealand’s prized Cheddar cheeses are typically made from unpasteurized milk from grass-fed cows, with flavors produced by a particular cocktail of local lactobacilli cultures, and coagulated with animal rennet. Once the Center for Dairy Research had developed a recipe for the cheese that was to be called Edun White Cheddar, the Homans asked Jon Metzig to make it for them at Willow Creek Creamery.

With that success, the Homans asked John Jaeggi at the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Dairy Research to suggest another cheese for the Red Barn milk. “He suggested New Zealand Cheddar as a model for the Red Barn,” Terry said. “That style lets the natural grass flavors come through the Cheddar. We agreed that was a perfect fit.” New Zealand’s prized Cheddar cheeses are typically made from unpasteurized milk from grass-fed cows, with flavors produced by a particular cocktail of local lactobacilli cultures, and coagulated with animal rennet. Once the Center for Dairy Research had developed a recipe for the cheese that was to be called Edun White Cheddar, the Homans asked Jon Metzig to make it for them at Willow Creek Creamery.

Metzig is a fourth-generation cheesemaker who grew up working at his family’s cheese plant and eventually became the youngest Wisconsin Master Cheesemaker in the state’s history. Jointly sponsored by the Wisconsin Center for Dairy Research, the University of Wisconsin’s Extension Service and the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board, the Wisconsin Master Cheesemaker Program requires its applicants to have held a Wisconsin cheesemaker license for a minimum of 10 years before they can qualify to embark on a three-year training program and apprenticeship that ends in a rigorous written examination, and finally, certification as a Master Cheesemaker for a particular variety of cheese. Applicants may certify in only two types of cheese each time they go through the program. Jon Metzig is certified as a Master Cheesemaker for Cheddar and Colby cheeses. He makes Edun in 40-pound blocks for Red Barns on demand as the orders for the cheese come in. “We schedule that as needed on a per month basis. Sometimes in the busy season, there might be several days,” Terry said. “It depends on our orders and his schedule. We accommodate each other’s needs.”

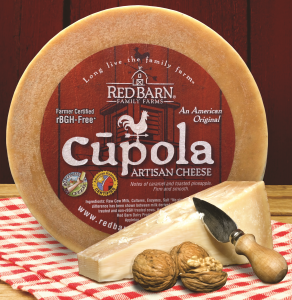

Then the Homans went back to the Center for Dairy Research with a request for a recipe for a unique American cheese. The result was Cupola, which has the sweet caramel flavor of a Gouda at the front, followed by the long tangy finish of a Parmesan. It’s often thought to resemble a Piave, a classic Italian cow milk cheese with a Protected Designation of Origin near the Piave River in the Dolomites region. “Cupola is just a really versatile cheese. It’s great with a glass of wine, but you can grate it,” said Paula. “It melts beautifully.”

Then the Homans went back to the Center for Dairy Research with a request for a recipe for a unique American cheese. The result was Cupola, which has the sweet caramel flavor of a Gouda at the front, followed by the long tangy finish of a Parmesan. It’s often thought to resemble a Piave, a classic Italian cow milk cheese with a Protected Designation of Origin near the Piave River in the Dolomites region. “Cupola is just a really versatile cheese. It’s great with a glass of wine, but you can grate it,” said Paula. “It melts beautifully.”

For this cheese, the Homans asked Katie Fuhrmann, the Head Cheesemaker at her family’s LaClare Farms, to lend her skills. A goat dairy, La Clare Farms is currently best known for its Standard Market Cave Aged Chandoka, a mixed milk cheese in the style of a New Zealand Cheddar, made by Fuhrmann at LaClare Farms and aged in the caves at the Standard Market in Illinois. Standard Market Cave Aged Chandoka won the first place award for American Originals at the 2015 American Cheese Society Judging and Competition and then went on to tie for second place in the Best of Show category.

Most recently, Red Barn brought out a Monterey Jack in 2016 that’s made by the Hintz family at Springside, and then went back to Metzig to make Le Rouge, which was introduced in limited release in 2016. It’s a washed-rind alpine-style cheese with a reddish-orange edible rind made from an original recipe and aged eight to nine months before sale. “When you taste it, it’s reminiscent of a French Comte,” Terry said. “It hearkens back to the traditions of our Red Barn Family Farms.”

Most recently, Red Barn brought out a Monterey Jack in 2016 that’s made by the Hintz family at Springside, and then went back to Metzig to make Le Rouge, which was introduced in limited release in 2016. It’s a washed-rind alpine-style cheese with a reddish-orange edible rind made from an original recipe and aged eight to nine months before sale. “When you taste it, it’s reminiscent of a French Comte,” Terry said. “It hearkens back to the traditions of our Red Barn Family Farms.”