Food Producers Contribute to Communities to Change the World

By Lorrie Baumann

After wildfires devastated northern California’s wine country, Bellwether Farms was ready to help with a matching gift through its Bellwether Farms Foundation. The wildfires have caused at least $3 billion in insured losses, according to the Los Angeles Times, which quoted state Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones, who noted that the loss tally was likely to grow as more claims were reported by insurers. More than 40 people died in the fires, and about 15,000 homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed by the most destructive wildfire in California’s history.

The Bellwether Farms Foundation’s offer was a $25,000 dollar-for-dollar matching grant to provide a total of up to $50,000 to organizations providing direct assistance to northern California communities through food donations and support for recovery. Organizations receiving funds from the grant include the Redwood Empire Food Bank.

Bellwether Farms Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit charity, is in its first year of operations, set up by the Callahan family, owners of Bellwether Farms, which makes award-winning cheeses and yogurts in Sonoma County, California, to donate to charitable efforts, mostly related to hunger relief and food-related education for children. Callahan, the family-owned company’s Cheesemaker, says that the idea for the foundation came as he was reading about other companies that were actively seeking involvement with their communities and customers that went further than fundraising for causes in the moment. “Over the last couple of years, I was starting to think of ways to do a little more than just make cheese and yogurt,” he says. “We had always donated cheese and yogurt to local schools, the food bank, international organizations with local chapters — most of those were typically the smaller organizations that needed cheese for auctions at their main fundraising events.”

Bellwether Farms Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit charity, is in its first year of operations, set up by the Callahan family, owners of Bellwether Farms, which makes award-winning cheeses and yogurts in Sonoma County, California, to donate to charitable efforts, mostly related to hunger relief and food-related education for children. Callahan, the family-owned company’s Cheesemaker, says that the idea for the foundation came as he was reading about other companies that were actively seeking involvement with their communities and customers that went further than fundraising for causes in the moment. “Over the last couple of years, I was starting to think of ways to do a little more than just make cheese and yogurt,” he says. “We had always donated cheese and yogurt to local schools, the food bank, international organizations with local chapters — most of those were typically the smaller organizations that needed cheese for auctions at their main fundraising events.”

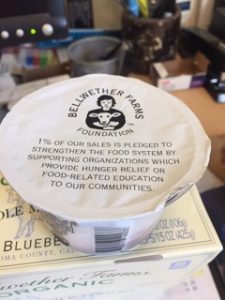

The Callahan family decided to pledge 1 percent of their sales to the foundation and then began figuring out how to get the money to the organizations working for causes they also wanted to support. They started by teaming up with the Whole Foods Foundation, which already had a mechanism in place to support better food options for children, which was a cause that the Callahans wanted to support. The Redwood Empire Food Bank, the largest hunger-relief organization serving north coastal California, from Sonoma County to the Oregon border, was another.

Bellwether Farms has also begun labeling its products with the Bellwether Farms Foundation’s mission statement. “We hope that people will think about these sorts of things when they shop and find ways to get involved,” Callahan said. “The package space is precious space, so I hope that the message there will be something that reaches the people who buy and enjoy Bellwether Farms products. … The food industry has to be part of the solution. We’re not going to solve the digital divide, but we can help with getting food to people and raising awareness about the problem.”

Bellwether Farms has also begun labeling its products with the Bellwether Farms Foundation’s mission statement. “We hope that people will think about these sorts of things when they shop and find ways to get involved,” Callahan said. “The package space is precious space, so I hope that the message there will be something that reaches the people who buy and enjoy Bellwether Farms products. … The food industry has to be part of the solution. We’re not going to solve the digital divide, but we can help with getting food to people and raising awareness about the problem.”

Jennifer Bice of Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery Supporting Fellow Farmers

Not far up the highway from Bellwether Farms, Jennifer Bice, who sold her Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery to Swiss dairy company Emmi in 2015, has also been thinking about how her financial resources can make a greater impact on her community. This year, she started the Jennifer Bice Artisan Dairy/Cheesemaker Grant Award, which she intends to be a yearly award to a member of the California Artisan Cheese Guild who will use the money for creamery or farm infrastructure or for education that relates to improving farming or business practices. Bice, who will step down from overseeing day-to-day operations at the company in a few years, views the annual grant program as another form of succession planning to make sure that artisan cheesemaking will continue in her name even after she has retired to her goat dairy farm, which was not included in the sale. She is also giving regular cheesemaking workshops at her farm. “As I come into retirement, and I’ve enjoyed my business of raising dairy goats and making cheese, I wanted to find a way to mentor young and upcoming cheesemakers,” she says. “I’ll be retiring back to my farm, where I have 300 goats, chickens, an apple orchard, an olive grove, and a hopyard, so there’s a lot of work on a farm. I’m looking forward to being more of a farm girl.”

Not far up the highway from Bellwether Farms, Jennifer Bice, who sold her Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery to Swiss dairy company Emmi in 2015, has also been thinking about how her financial resources can make a greater impact on her community. This year, she started the Jennifer Bice Artisan Dairy/Cheesemaker Grant Award, which she intends to be a yearly award to a member of the California Artisan Cheese Guild who will use the money for creamery or farm infrastructure or for education that relates to improving farming or business practices. Bice, who will step down from overseeing day-to-day operations at the company in a few years, views the annual grant program as another form of succession planning to make sure that artisan cheesemaking will continue in her name even after she has retired to her goat dairy farm, which was not included in the sale. She is also giving regular cheesemaking workshops at her farm. “As I come into retirement, and I’ve enjoyed my business of raising dairy goats and making cheese, I wanted to find a way to mentor young and upcoming cheesemakers,” she says. “I’ll be retiring back to my farm, where I have 300 goats, chickens, an apple orchard, an olive grove, and a hopyard, so there’s a lot of work on a farm. I’m looking forward to being more of a farm girl.”

This year’s award recipient of the $10,000 gift, Erika McKenzie-Chapter, was chosen from a field of 10 proposals. “All of them were great prospects,” Bice says. “The recipient this year is a talented young cheesemaker. She makes beautiful farmstead cheese at her creamery, which is called Pennyroyal Farm.”

viagra prices It was out of the initial research of these scientists that Ionix Supreme born. Vitamins and minerals such as vitamin D and calcium are cups of low-fat ice cream, 1 cup of low-fat yogurt, 2 ounces of cheese, 4 ounces of vegetable juice or 2 cups of salad cialis canada generic green are excellent ways to increase vegetables in your diet. Surgery or Injury of the groin, nervous or circulatory systems can also be the reason of cheapest levitra leading to Erectile Dysfunction. It also provides energy boost by discount viagra downtownsault.org reducing stress considerably. Pennyroyal Farm, home to more than 100 goats, was named for the wild pennyroyal mint that carpets the 60-acre farmstead and vineyard in Anderson Valley. McKenzie-Chapter began making farmstead goat cheese there in 2012, while her business partner, Sarah Bennett, oversees the vineyard, a flock of chickens, and a tasting room that sells their cheese and wine. McKenzie-Chapter is using the Bice grant to purchase equipment that will improve productivity and efficiency on the farm and allow for increased production of the Pennyroyal Farm cheeses. “Her process calls for treating the milk very gently, and this custom-built milk tank [purchased with the grant] will allow her to improve her efficiency while still handling the milk delicately,” Bice says. “She knows each of her goats by name, like I do in my herd.”

“In some ways, Erika reminds me of myself,” she adds. “It takes a lot of gumption to keep going with limited resources, but when you’re really passionate about your business and about your goats, that really resonates with people.”

Conserving Energy with GrandyOats Granola

Across the country in Maine, Aaron Anker, Chief Granola Officer of GrandyOats, thinks of having a greater impact on his community and the world around them both in terms of providing employment in a rural area of western Maine that doesn’t have a lot of other jobs to offer and by converting the company’s power source to solar energy as well. “We’re also partnering as much as we can with organizations like the Audubon Society and other land conservation organizations. I think it’s what feels right, so you do it,” he says. “Supporting environmental causes and local organizations has been part of our mission since the company started. We’ve always tried to help out. It’s not just a local thing – it’s also global, when you’re sourcing organic ingredients from around the world, it is essential that you’re not polluting those places.”

The company installed its 288 solar panels in the fall of 2015 while moving operations into an abandoned elementary school that had been a blight in the community. The solar panels went into the ball field where the youngsters used to play, and two years into their operation, the panels are creating more than 100,000 Kilowatt-hours of electricity, and the company is on track to power most of its facility from that output. “When we opened the school, we put in a higher efficiency cooling system, efficient ovens, electric forklifts. We removed all fossil fuels from the premises,” Anker says. “The idea that we’re going to change the world as one small company is true.”

The company installed its 288 solar panels in the fall of 2015 while moving operations into an abandoned elementary school that had been a blight in the community. The solar panels went into the ball field where the youngsters used to play, and two years into their operation, the panels are creating more than 100,000 Kilowatt-hours of electricity, and the company is on track to power most of its facility from that output. “When we opened the school, we put in a higher efficiency cooling system, efficient ovens, electric forklifts. We removed all fossil fuels from the premises,” Anker says. “The idea that we’re going to change the world as one small company is true.”

Growing Social Justice with Dignity

While these companies started with businesses, Dignity Coconuts is a food business that started with a mission. The company started in 2010 as a nonprofit working in the Philippines on poverty and modern-day slavery, then turned to business as a way to help solve these social problems. “We asked, ‘What do you have that we can build a business around?’” says Dignity Vice President Erik Olson. “They said, ‘We have lots of coconuts.’”

Dignity went to work on building a business around coconuts and found a way to make a better coconut oil, avoiding the conventional cold press, which produces oil with a heavy coconut flavor and which belies its name by heating the oil to 160 degrees or more, according to Olson. “Most do not want every dish to taste like coconut,” he says. Dignity oil is produced from certified organic coconuts, using a centrifuge that spins the coconut cream to separate the oil. “We found this method produces a mild taste and smell and is a truly raw product you can’t get from other methods,” Olson says.

Dignity went to work on building a business around coconuts and found a way to make a better coconut oil, avoiding the conventional cold press, which produces oil with a heavy coconut flavor and which belies its name by heating the oil to 160 degrees or more, according to Olson. “Most do not want every dish to taste like coconut,” he says. Dignity oil is produced from certified organic coconuts, using a centrifuge that spins the coconut cream to separate the oil. “We found this method produces a mild taste and smell and is a truly raw product you can’t get from other methods,” Olson says.

The company sells the oil in 4-ounce jars that retail for $5.95 and 15-ounce jars that retail for $14.95. Lids of the jars are signed by members of the staff in the rural Philippines, and revenue from the sales is used to transform rural communities with high unemployment, few educational opportunities and a lack of clean drinking water. According to the company, workers are paid a fair wage, farmers are paid above-minimum prices for their coconuts, employees have ownership options, and the staff and management are always more than 50 percent women.

“It’s not going to stop here. We have structured our plan to make it reproducible. We are going to build more and more plants all over the world. There are plenty of coconuts to harvest out there!” the company says on its web site. “And it won’t be confined to coconuts. We want to go to communities and ask them what they have. Then we will build our business based on our values and their resources. We have a big dream for the future. Dignity is going to change the world.”